THE CULTURE MAP

|

|

8 dimensions

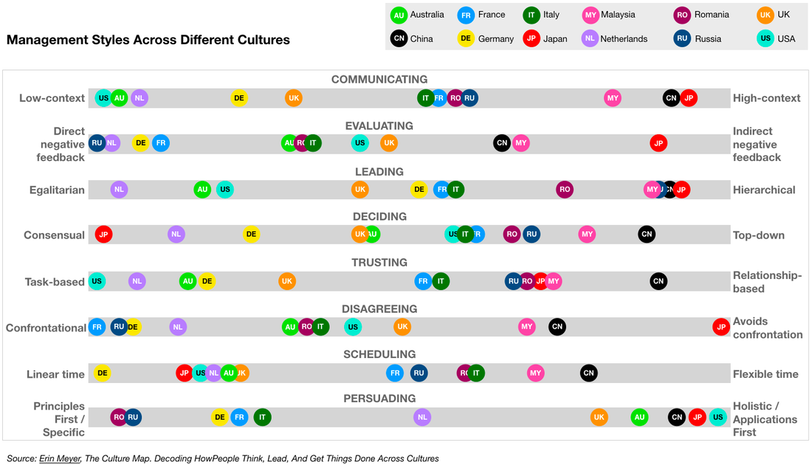

The Culture Map shows positions along these eight scales for a large number of countries, based on surveys and interviews. These profiles reflect, of course, the value systems of a society at large, not those of all the individuals in it, so if you plot yourself on the map, you might find that some of your preferences differ from those of your culture.

|

1. Communicating.

When we say that someone is a good communicator, what do we actually mean? The responses differ wildly from society to society. Erin Meyer compares cultures along the Communicating scale by measuring the degree to which they are high- or low-context, a metric developed by the American anthropologist Edward Hall. In low-context cultures, good communication is precise, simple, explicit, and clear. Messages are understood at face value. Repetition is appreciated for purposes of clarification, as is putting messages in writing. In high-context cultures, communication is sophisticated, nuanced, and layered. Messages are often implied but not plainly stated. Less is put in writing, more is left open to interpretation, and understanding may depend on reading between the lines. |

QUIZ TEST: HOW YOU DECODE CULTUREWhen we say someone is a good communicator, what do we actually mean?

Take our test and assess your ability to decode communication across countries. |

2. Evaluating.

All cultures believe that criticism should be given constructively, but the definition of “constructive” varies greatly. This scale measures a preference for frank versus diplomatic negative feedback. Evaluating is often confused with Communicating, but many countries have different positions on the two scales. The French, for example, are high-context (implicit) communicators relative to Americans, yet they are more direct in their criticism. Spaniards and Mexicans are at the same context level, but the Spanish are much more frank when providing negative feedback.

3. Persuading.

The ways in which you persuade others and the kinds of arguments you find convincing are deeply rooted in your culture’s philosophical, religious, and educational assumptions and attitudes. The traditional way to compare countries along this scale is to assess how they balance holistic and specific thought patterns. Typically, a Western executive will break down an argument into a sequence of distinct components (specific thinking), while Asian managers tend to show how the components all fit together (holistic thinking). Beyond that, people from southern European and Germanic cultures tend to find deductive arguments most persuasive, whereas American and British managers are more likely to be influenced by inductive logic. The research into specific and holistic cognitive patterns was conducted by Richard Nisbett, an American professor of social psychology, and the deductive/inductive element is Erin's work.

4. Leading.

This scale measures the degree of respect and deference shown to authority figures, placing countries on a spectrum from egalitarian to hierarchical. The Leading scale is based partly on the concept of power distance, first researched by the Dutch social psychologist Geert Hofstede, who conducted 100,000 management surveys at IBM in the 1970s. It also draws on the work of Wharton School professor Robert House and his colleagues in their GLOBE (global leadership and organisational behaviour effectiveness) study of 62 societies.

5. Deciding.

This scale, based on Erin's work, measures the degree to which a culture is consensus-minded. We often assume that the most egalitarian cultures will also be the most democratic, while the most hierarchical ones will allow the boss to make unilateral decisions. This isn’t always the case. Germans are more hierarchical than Americans, but more likely than their U.S. colleagues to build group agreement before making decisions. The Japanese are both strongly hierarchical and strongly consensus-minded.

6. Trusting.

Cognitive trust (from the head) can be contrasted with affective trust (from the heart). In task-based cultures, trust is built cognitively through work. If we collaborate well, prove ourselves reliable, and respect one another’s contributions, we come to feel mutual trust. In a relationship-based society, trust is a result of weaving a strong affective connection. If we spend time laughing and relaxing together, get to know one another on a personal level, and feel a mutual liking, then we establish trust. Many people have researched this topic; Roy Chua and Michael Morris, for example, wrote a landmark paper on the different approaches to trust in the United States and China. I have drawn on this work in developing my metric.

7. Disagreeing.

Everyone believes that a little open disagreement is healthy, right? The recent American business literature certainly confirms this viewpoint. But different cultures actually have very different ideas about how productive confrontation is for a team or an organisation. This scale measures tolerance for open disagreement and inclination to see it as either helpful or harmful to collegial relationships. This is my own work.

Scheduling.

8. Scheduling.All businesses follow agendas and timetables, but in some cultures people strictly adhere to the schedule, whereas in others, they treat it as a suggestion. This scale assesses how much value is placed on operating in a structured, linear fashion versus being flexible and reactive.

All cultures believe that criticism should be given constructively, but the definition of “constructive” varies greatly. This scale measures a preference for frank versus diplomatic negative feedback. Evaluating is often confused with Communicating, but many countries have different positions on the two scales. The French, for example, are high-context (implicit) communicators relative to Americans, yet they are more direct in their criticism. Spaniards and Mexicans are at the same context level, but the Spanish are much more frank when providing negative feedback.

3. Persuading.

The ways in which you persuade others and the kinds of arguments you find convincing are deeply rooted in your culture’s philosophical, religious, and educational assumptions and attitudes. The traditional way to compare countries along this scale is to assess how they balance holistic and specific thought patterns. Typically, a Western executive will break down an argument into a sequence of distinct components (specific thinking), while Asian managers tend to show how the components all fit together (holistic thinking). Beyond that, people from southern European and Germanic cultures tend to find deductive arguments most persuasive, whereas American and British managers are more likely to be influenced by inductive logic. The research into specific and holistic cognitive patterns was conducted by Richard Nisbett, an American professor of social psychology, and the deductive/inductive element is Erin's work.

4. Leading.

This scale measures the degree of respect and deference shown to authority figures, placing countries on a spectrum from egalitarian to hierarchical. The Leading scale is based partly on the concept of power distance, first researched by the Dutch social psychologist Geert Hofstede, who conducted 100,000 management surveys at IBM in the 1970s. It also draws on the work of Wharton School professor Robert House and his colleagues in their GLOBE (global leadership and organisational behaviour effectiveness) study of 62 societies.

5. Deciding.

This scale, based on Erin's work, measures the degree to which a culture is consensus-minded. We often assume that the most egalitarian cultures will also be the most democratic, while the most hierarchical ones will allow the boss to make unilateral decisions. This isn’t always the case. Germans are more hierarchical than Americans, but more likely than their U.S. colleagues to build group agreement before making decisions. The Japanese are both strongly hierarchical and strongly consensus-minded.

6. Trusting.

Cognitive trust (from the head) can be contrasted with affective trust (from the heart). In task-based cultures, trust is built cognitively through work. If we collaborate well, prove ourselves reliable, and respect one another’s contributions, we come to feel mutual trust. In a relationship-based society, trust is a result of weaving a strong affective connection. If we spend time laughing and relaxing together, get to know one another on a personal level, and feel a mutual liking, then we establish trust. Many people have researched this topic; Roy Chua and Michael Morris, for example, wrote a landmark paper on the different approaches to trust in the United States and China. I have drawn on this work in developing my metric.

7. Disagreeing.

Everyone believes that a little open disagreement is healthy, right? The recent American business literature certainly confirms this viewpoint. But different cultures actually have very different ideas about how productive confrontation is for a team or an organisation. This scale measures tolerance for open disagreement and inclination to see it as either helpful or harmful to collegial relationships. This is my own work.

Scheduling.

8. Scheduling.All businesses follow agendas and timetables, but in some cultures people strictly adhere to the schedule, whereas in others, they treat it as a suggestion. This scale assesses how much value is placed on operating in a structured, linear fashion versus being flexible and reactive.

CROSS-CULTURAL LEADERSHIP PROGRAM

Empower your managers to lead multinational teams effectively by decoding how cultural differences impact international business.

Equip them with practical and actionable tools in an engaging environment:

Empower your managers to lead multinational teams effectively by decoding how cultural differences impact international business.

Equip them with practical and actionable tools in an engaging environment:

- Compare how several cultures build trust, give negative feedback, and make decisions.

- See how you compare to others of your own culture

- Map your individual and team results to that of various other countries